Rollerland

Rollerland was used as a boy’s dormitory (ages 13-18) and a wash house for everyone. Nearby (where the Pacific Coliseum now stands) were two large mess halls, segregated for men and women. The BC Security Commission served 1,542,371 meals to Japanese Canadians, with a raw food cost of only nine cents per meal.

The food served in tin plates and bowls was terrible and due to unsanitary conditions, everyone in the park suffered with severe cases of diarrhea. One day we protested by staging a one day hunger strike. Everyone went to the mess hall, got their food, and dumped it on the table and left. But it didn’t do much good. – Tom Tagami

They gave us cold porridge. It was hard and lumpy... My mom used to go to a small store nearby. She used to buy us an orange and a doughnut... for breakfast. We never got sick so I guess the vitamins in the orange helped. – Mae (née Doi) Oikawa

The food quality was poor, and the tin plates were noisy. Some of the community members found the diet of stew, potatoes, gruel, bread, and butter very difficult - many missed rice, fish, fresh fruit and vegetables.

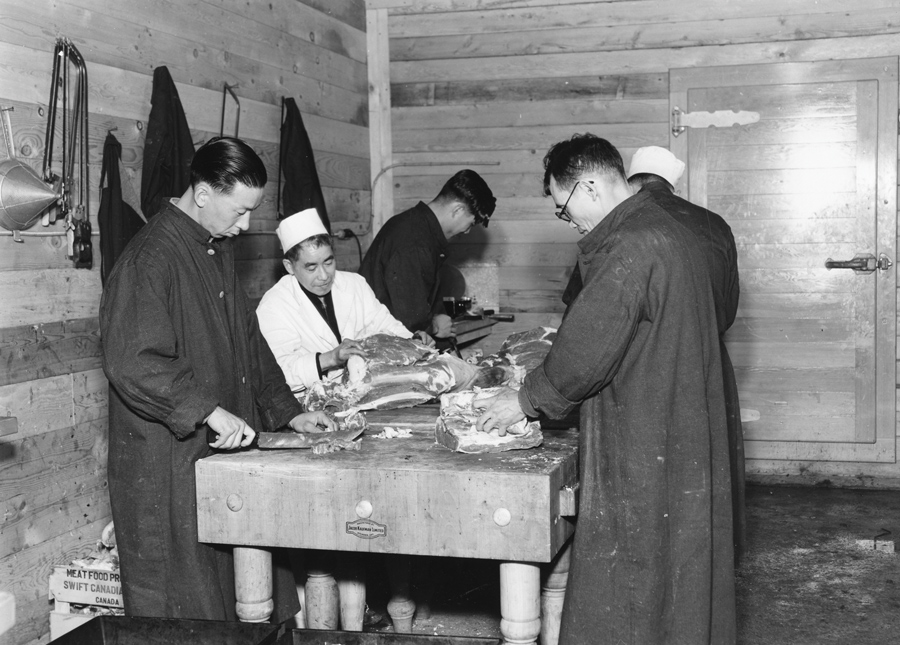

Food was mostly prepared on site, with special rooms for meat cutting, baking, preparing milk, and separate kitchens for the general populace.

A canteen was available for people who had money to spend, but mostly contained candy, pop and snack foods. A small store located across Renfrew Street took special orders through the fence.

Three times a day, there were long lines for food and the service was slow. Food was often very cold by the time they sat down at the long tables.

Separate dining areas were available for the young children and babies, and for the hospital patients. Mary Kitagawa remembers that “We were fed in the poultry section at rough tables with tin plates, and our hair, skin and clothes were soon permeated with the stench of animal urine and feces.”